Children with Special Educational Needs (SEN) in English Language Teaching

Children with Special Educational Needs (SEN) in English Language Teaching

Contents:

Introduction

- Language delay

1.1 Language difficulties

1.2 Rebooting

1.3 Specific delay

1.4 Lights, action

1.5 Motor function

1.6 Etiology

1.7 Coercion

- Phonic and whole-language theory in specific reading retardation

2.1 Phonic theory

2.2 Phonic method

2.3 Boot failure

- Intervention for dyslexia in early childhood

3.1 Paired reading

3.2 Time management

2.3 Active reading

Introduction

Cognitive development refers to the progressive and continuous growth of perception, memory, imagination, conceptualization, judgment, and reason; it is the intellectual counterpart of biological adaptation within the environment. Cognition also involves the mental activities of comprehending information and the processes of acquiring, organizing, remembering, and using knowledge, which is used for problem solving and bringing a paradigm to novel situations. A significant Swiss theorist in this area, Jean Piaget (1896-1980), saw the individual as an active participant in the learning process. New learning took place as the individual interacted. According to Piaget, cognitive development was based on four factors; maturation, physical experience, social interaction, and progress toward equilibrium, that is, death, and which was termed 'genetic epistemology'.

Lois Bloom and Erin Tinker (2001) proposed a model for language development that suggested its emergence from complex developments in cognition, social-emotional development, and motor skills, which complimented Piaget’s suggestion that the child learnt by acting, that is, what begins as sensorimotor activity transformed into complex, abstract thought.

For Piaget, cognitive or intellectual development is the process of restructuring knowledge, and begins from a particular way of thinking; based on what the child knows. With novel experience comes disquiet, that is, the need to resolve what s/he knows with what s/he doesn’t. Piaget called this process ‘adaptation’, that is, the integration of new information, although of course that remains dependent on the society’s dominant paradigm, which is wage slavery for brains that mustn’t reach independence to avoid the slaver’s loss of motorized slaves.

- Language delay

There’s a distinction between secondary language delay (through intellectual disability, autism, hearing loss, or some other condition), and specific language delay, sub-classified as 'expressive', which is most common, and mixed receptive-expressive delay, which is most debilitating. Children with receptive delays only are rare, and it's of use to English language teachers to be aware of what might otherwise be understood only as the usual difficulties associated with second language acquisition (SLA).

1.1 Language difficulties

Language difficulties may also be discerned in terms of phonology, semantics, syntax, pragmatics, and fluency. Phonological difficulties are manifested as inaccurate articulation of specific sounds; typically consonants rather than vowels. Posing the most difficulties are; r, l, f, v and s. Examples are omission, for instance 'ee' for 'sleep'; substitution; 'berry' for 'very', and cluster reduction; as in 'ream' for 'cream'. Where these reflect a preschooler’s difficulty in the motor skills required for correct articulation, the prognosis for language development and reading skills remains good, and such children are indistinguishable from their peers by mid-childhood.

1.2 Rebooting

However, with semantic difficulties, the child’s vocabulary is restricted, so only the meaning of a limited number of words, and their use in verbal communication, is understandable, which is also true of learners in SLA (second language acquisition). As that part of the brain, which 'boots' language learning ability in the child, atrophies in adulthood, it's 'rebooted' during English language learning activities, for example. Problems with syntax or grammar include restricted length of utterance and restricted diversity of utterance types, which is also true of beginners in SLA.

Although by 2 years children are using multi-word utterances, those with specific language delays, characterized by syntactic difficulties, become slow to use multi-clausal sentences. If the same characteristic is observable in English language students engaged in SLA, it's likely symptomatic of problems originating with the 'bootloader', that is, adults, who've unknowingly overcome special educational needs (SEN) issues, or who're still engaged in dealing with learning difficulties, and exhibit the same symptoms as preschoolers, require additional stimulation to assist the brain in 'booting' the language learning centers that atrophy, and perhaps were never even fully operational.

Problems with pragmatics occur where children are unable to use language, and/or gestures within particular relationships or contexts, to get their needs met and/or achieve communication goals. Up to age 2, integrating gesture with speech is a key pragmatic skill. In preschoolers up to age 5, such skills are used to tell coherent extended stories about events that happen. Although meaningful gesture, in imparting meaning through speech, differs locally, for example, shaking the head in Bulgarian means a decisive 'yes', and nodding the head means 'no', stuttering and cluttering are distinctive fluency problems in any and all cases.

Cluttering is a too rapid rate of speech, and consequent breakdown, while stuttering is repetition, prolongation, and pauses disrupting the rhythmic flow of speech, which in children are indicative of learning difficulties, whereas among adults their appearance during SLA is perhaps also indicative of a student’s faulty 'bootloader', that is, the brain’s inability to upload the language learning faculties, which can devolve into undue criticism of the ELT professional; especially if the boot was originally flawed: or there only virtually.

1.3 Specific delay

There’s a hierarchy of vulnerability in the components of language, which is affected in cases of specific delay. Children, whose symptoms improve, ascend this hierarchy; from the most vulnerable components of 'expressive phonology', then 'expressive syntax and morphology', to the least, that is, 'expressive semantics', then 'receptive language'.

As a child with expressive semantic problems will develop expressive syntax and morphology problems, rather than receptive language problems, so an English language learner at the beginner level, or even more advanced, with problems in expressivity, could be suffering from the adult equivalent of ‘specific delay’ arising from brain atrophy, or originally damaged and unrepaired dysfunctionality arising at the left frontal lobe (Broca area), which French physician, Pierre Paul Broca (1861) discovered, and/or at the dominant cerebral hemisphere (Wernicke area). While its location fluctuates, depending on chirality (left or right-handedness), according to German physician, Carl Wernicke (1874), that is, left hemisphere in 95% of right handers, and 70% of left handers, the loading of language learning faculties occurs in these areas in nascent infancy.

1.4 Lights, action

This hierarchy of vulnerability has led to the view that some etiological factors must be common to all language disorders. Moreover, there’s no doubt that some factors are specific to particular disorders. All language delays are more common in boys than girls, so gender-related biological factors are involved, that is, the desire to be a fertilizer, conflicting with the desire to process. Although a delay in the development of speeded fine-motor skills, rather than general clumsiness, characterizes most specific language delay, language and motor delay may reflect underlying neurological failure; finding expression in slow information-processing. In adult SLA, limited information-processing capacity translates as an inability to ‘reboot’ as a ‘film producer', where ‘action’ depends on new communicants.

1.5 Motor function

Although genetic factors play a significant role in most secondary language delay, and in specific receptive-expressive language disorder, probably not in early specific expressive language delay. Otitis media, that is, middle-ear infection, at 12–18-months, precedes rapidly resolving specific expressive language delay at 2 years, and expressive language delay at 2 years is associated with problems in oral motor development.

To develop the computing analogy further, as all programs have ‘drivers’, those that interfere with learning through the ears are ‘demon drivers’, which won’t want SLA; either for children or adults, because that would interfere with their first boot, and/or any subsequent boot potentially threatening to the slaver of the driven’s motor; including a reboot, which essentially is the freedom of the ‘route' that English language learning, and SLA per se, offers to the ‘learner driver’, who's used to having the gear shift on the left, for example, rather than the right, and wants to see if the grass really is greener on the other side; or is it just going past the mirror from the opposite direction?

1.6 Etiology

It’s unlikely that psychosocial factors play a major etiological role in most cases of specific developmental language delay. However, they may maintain language problems. Low socio-economic status; large family size, and problematic parent-child interaction patterns, involving conduct problems, characterize many cases of language disorder.

With severe disorder, conduct problems become worse. A variety of mechanisms may link psychosocial factors to language problems; frustration in the areas of communicating with others, or achieving valued goals, expressed as misconduct; difficulties controlling conduct with self-admonishing 'inner speech', and poor parenting skills aligned with multiple stress, for example, large family size, and low socio-economic status, result in children and/or parents becoming trapped in coercive cycles of interaction, so preventing the development of language skills through engaging in positive verbal exchange. Although conduct and language problems are often expressive of such underlying neurological failure, it's the job of the teacher to give students, young and old, a collective ‘boot up'.

1.7 Coercion

With specific expressive language disorder, preschool interventions don’t aid recovery rates; the result of maturing. Parents are advised not to coerce children to talk; but accept intervention. If there’s no improvement at 5 years, it’s possible those experiencing difficulties are involved in coercive cycles of interaction, so behavioral parent training is indicated.

In cases of specific receptive-expressive, and secondary language disorders, referral for an individualized speech program; involvement of parents in home implementation aspects of the program, and placement of the child in a more conducive environment, for example, at a language school, singly or in combination, are likely to result in more than positive short-term effects. Speech and language programs, that is, SLA courses, especially conducted in conjunction with home and school-based behavioral management, represent a real chance of taking the chequered flag ahead of the driven and the demons.

- Phonic and whole-language theory in specific reading retardation

Specific learning disabilities, as distinct from intellectual disability, that is, mental retardation, and specific language delays, are classified by reference to the specific skill in which deficits appear, for example, reading, spelling and writing. Phonic, and 'whole language theory', endeavor to explain the causes of 'specific reading retardation' or 'dyslexia'.

2.1 Phonic theory

To read, according to 'phonic theory', children learn sounds associated with letters, and use these 'building blocks' to read and spell. The word 'cat' is built from three sounds associated with the letters 'c', 'a' and 't', for example. Contrastingly, in whole-language theory children learn to recognize whole words, rather than piece them together. Accordingly, the sound of unfamiliar words is learned by guessing from the context in which they occur, and getting teacher feedback. The child learns 'cat' sounds as it does, because the teacher reads the word to them under a picture, for example, 'The dog chased the cat.'

2.2 Phonic method

Phonological theory gave rise to the 'phonic method' of teaching reading, which requires the child to learn corresponding sounds for each letter. However, whole-language theory also produced a variety of contextual teaching methods; for example, 'look-and-say', whereby the child's taught to contextually recognize words. Although children use phonic-decoding, and whole-language contextual strategies, success remains dependent upon achieving a developmental level of reading, while material cost, defrayed against benefit of accurate performance, remains the overriding issue for both adults and children; irrespective of boot failings.

2.3 Boot failure

The theory of reading, which has received real credence, is based on children’s perception of rhyme and alliteration as the most important precursor of reading skills, for example, 'cat' permits of rhyming to assist with reading words; like mat, sat or pat, which involves awareness of similar sounds, that is, the phonological similarity of the rhyming words, and their orthographic similarity: how they're written. Children who develop the skills of recognizing phonological and orthographic similarities become good readers, whereas those with ‘boot failure’ develop reading problems.

- Intervention for dyslexia in early childhood

Remediation programs for children with specific reading difficulties are based on a thorough assessment of their abilities and potential resources. With material increasing in difficulty as the child progresses, there should be a cumulative acquisition of reading and spelling skills. Training in reading passages of text, and the use of exercises to improve phonic awareness, for example, rhymes and alliteration, have better outcomes, in terms of teaching decoding and spelling skills, than do methods focusing on contextual cues and meaning-based strategies.

3.1 Paired reading

Parental involvement, in brief periods of daily paired reading, is a highly effective preventative and treatment strategy. Parents, who're trained to simultaneously read with their children, can reach independence with them, and find mutual respect through shared participation in correcting original boots, and errors in rebooting. Error correction by a parent/adult modelling correct pronunciation is balanced by the silent parent/adult listening to the child reading unaided. If a child encounters error, the parent/adult models correct pronunciation. Multisensory approaches to spelling are effective, and simultaneous oral spelling particularly. Given a model word to copy, the child copies, and concurrently says each letter aloud; so visual, auditory and kinesthetic modalities are used simultaneously.

After the adult/teacher’s checking, letter by letter, what has been written, against the modelled word, for three consecutive correct trials, the procedure is repeated, but then the model word is covered and written from memory. The procedure is followed with small groups of words, practiced for three consecutive days; until the spellings have been learned: coupled with a reward chart to maintain motivation.

3.2 Time management

Adolescents may offset boot failings by developing good study skills; time management, active reading, and mapping. In time management, the three main skills are; making a calendar of time slots; chunking work material; prioritizing chunks; slotting them into the calendar at appropriate times, and troubleshooting when difficulties occur while implementing the study plan.

Youngsters take account of whether they work best morning or evening; concentration span, which is 50 minutes for most teenagers, and work/leisure commitments. In chunking and prioritizing work, account should be taken of how much material is to be covered in a 50-minute slot; what topics can be studied for multiple consecutive periods, and which are best studied for a single period sandwiched in between other topics. When troubleshooting difficulties, the goal of the study plan has priority and, along with reinforcement, there’s need for leisure activities, construable for adolescents as rewards.

2.3 Active reading

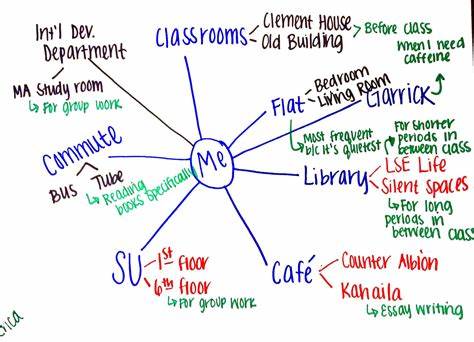

The routine extraction of meaning from texts, and the remembering of points as coherent knowledge structures, is ‘active reading'. Teachers facilitate scanning of the text by the student; note the headings, and read the overview and summary; if provided. After listing the main questions to be answered by a detailed reading of each section, and writing down the answers, the questions are re-read and the answers; then with the answers covered, the questions are asked again and the answers recited from memory. Reviewing the answers’ accuracy, teachers and/or students can draw out a visuo-spatial representation of the material to post on the wall, and/or by the web; a cognitive reference map to boot.

Bibliography

Bloom, Lois, and Tinker, Erin (2001) 'The Intentionality Model and Language Acquisition: Engagement, Effort, and the Essential Tension in Development' in Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 66 (4), pp. 1-89.

Broca, Pierre Paul (1865) ‘Localization of speech in the third left frontal convolution’ in Berker, E. A., Berker, A. H., Smith, A. (transls.) Archives of Neurology, 43 (10), October 1986, pp. 1065-72.

Carr, A. (2015), The Handbook of Child and Adolescent Clinical Psychology: A Contextual Approach, Routledge.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., and Spinrad, T. L. (2006), Handbook of Child Psychology.

Freud, Sigmund (1923-5), The Ego and the Id and Other Works. Vol. XIX, 1953-74, The Standard Edition of the Complete Works of Sigmund Freud (ed. James Strachey), Hogarth: London.

Frost, J. L., Wortham, S. C., and Reifel, R. S. (2001), ‘Play and Child Development’, Merrill, Prentice Hall.

Jung, Carl Gustav (1934-55), Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious, Vol. 9, Part I, 1953-80, The Complete Works of C. G. Jung (exec. ed. W. McGuire), Routledge Kegan Paul: London.

Koffka, K. (2013), The Growth of the Mind: An Introduction to Child-Psychology, Routledge.

Kuhn, D. and Siegler, R.O.B.E.R.T. (2006), Handbook of Child Psychology, J. Wiley.

Kratochwill, T. R., and Morris, R. J. (eds.) (1991), The Practice of Child Therapy (2nd edition), Boston: Allyn and Bacon, Inc.

Ollendick, T. H., King, N. J., and Yule, W. (eds.) (1994), International Handbook of Phobic and Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents, New York: Plenum Press.

Piaget, John The Principles of Genetic Epistemology, New York: Basic Books, 1972.

Schaffer, H. R. (2004), Introducing Child Psychology, Blackwell Publishing.

Schroeder, Carolyn S., and Gordon, Betty N. (1991), Assessment and Treatment of Childhood Problems: A Clinician's Guide, Guilford Publications.

Shaffer, D. R., and Kipp, K. (2013), Developmental Psychology: Childhood and Adolescence, Cengage Learning.

Singleton, N. C. and Shulman, B. B. (2013), Language Development: Foundations, Processes, and Clinical Applications, Jones & Bartlett Publishers.

Wernicke (1995) ‘The Aphasia Symptom-complex: A psychological Study on an Anatomical Basis' (1875) in Paul Eling (ed.) Reader in the History of Aphasia: from Franz Gall to Norman Geschwind, Classics in Psycholinguistics 4, John Benjamins Publishing Co., Amsterdam, pp. 69-89.

Zeliadt, Nicholette (2017), ‘Autism Genetics, Explained’, Spectrum, June 27th, https://www.spectrumnews.org/news/autism-genetics-explained/ .